Christmas Tree Ships

The Saga of the Rouse Simmons (1868 - 1912)

Chicago Lumber Trade

After the Civil War, Michigan and Wisconsin lumber centers - Muskegon, Manistique, Menominee, and Green Bay sent hundreds of schooner loads of lumber to the Chicago market. The geographic position made Chicago a great market - bordering the lake and backing onto the vast tree-poor prairie, Chicago was on the border of supply and demand.

Chicago’s demand for lumber grew after the 1871 fire that burned the central business district and the north side of the city. Before the ashes cooled, schooners arrived with cargoes of new building materials to shelter the homeless. Sailing ships made Chicago one of the world’s busiest ports. In the year of the Great Fire, more ships arrived in Chicago than in New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston combined.

Lumber was the most important product carried by ship to the city, it was the backbone of Lake Michigan Shipping. At the mouth of the Chicago River, pictured below in 1890, and on the west side of the city were the great lumberyards.

The Rouse Simmons

By 1898, when Hackley sold the Rouse Simmons, Muskegon was beginning its transition away from the lumber industry as its hinterland was logged off. The Simmons, however, continued in the lumber trade. Her ports of call increasingly were along Michigan’s Upper Peninsula - the last frontier of logging on Lake Michigan. The Rouse Simmons was 42 years old when she was acquired by Herman Shuenemann, a veteran lumber skipper of Chicago.

The last ships to dock in Chicago at the conclusion of the shipping season were the Christmas Tree Ships. The late November and early December voyages were extremely hazardous. Herman Schuenemann became known as "Captain Santa" for giving away many of his trees to the city’s poor. Captain Santa and his family sold Christmas trees from the deck of the schooner tied up in the Chicago River. Lights were strung from the schooner's bow to stern, and customers were invited to board the ship to choose their trees. In addition to selling Christmas trees, the Schuenemann’s made and sold wreaths, garlands, and other holiday decorations. Barbara Schuenemann and her three daughters helped make and sell these items as part of the family's holiday trade. The Schuenemanns bought vessels late in their sailing careers, purchasing the least-expensive, aged schooners, hoping for the last bit of life and profit from them in the lumber trade.

Shipwreck

On November 22, 1912, the Rouse Simmons, heavily laden with over 3,000 Christmas trees filling its hold, left the dock at Thompson, Michigan. The departure coincided with the beginnings of a tremendous winter storm on the lake that sent several other ships to the bottom of the lake. The Rouse Simmons met her end on the following day, November 23, 1912, when she was lost with all hands on deck. The twilight years of this ship reveal some hard truths about the lumber trade. A large, well-run company like Hackley’s could afford to keep its vessels in good trim, yet a portion of the lumber fleet was made up of schooners, owned and managed by their captains. The short hauls and buoyant cargoes of the lumber trade encouraged captains to overload vessels and delay long-term maintenance.

The Legacy Lives On

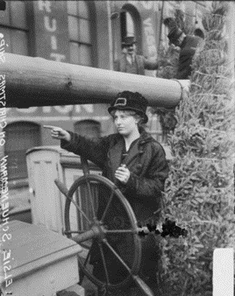

Grief stricken, at first, Barbara and her daughters refused to believe the Simmons was lost. Elsie Schuenemann, age 23 in 1915, exemplified courage beyond her years. Elsie began weaving Christmas wreaths and making plans to dock a borrowed ship in the Chicago harbor to sell salvaged trees picked up along the beaches of Lake Michigan just after her father died. Miss Elsie Schuenemann became the backbone of the operation and would also acquire the nickname “The Queen of Christmas Trees”. Following Barbara’s death in the summer of 1933, her daughters continued on for a few more years.

Elsie Schunemann, 1915

Hazel and Pearl Schunemann, 1917

Elsie Shunemann, 1928

Shuenemann's story inspired poems, books, songs, paintings, and a musical that is put on across the United States every holiday season. Evergreens are symbolic of strength and courage. Appropriately, the Schuenemann memory will forever be linked to the trees they loved.

A diver discovered the wreck of the Rouse Simmons 9 miles northeast of Two Rivers, WI. The Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary was established this year. The Sanctuary is one of 15 marine sanctuaries administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The Wisconsin Shipwreck Sanctuary will protect 36 shipwrecks that possess exceptional historic value. Historical research suggests that nearly 60 shipwrecks are yet to be discovered in the sanctuary. The sanctuary will bring new opportunities for research, resource protection, educational programming, and community engagement. Learn more here.

Learn More

We are proud to help pass along the legacy of the Rouse Simmons at the Chicago Maritime Museum. To learn more, please visit and see two models of the Rouse Simmons currently on display.

The museum is home to a vast Christmas Tree Ship collection including a copy of the nearly 900 page Christmas Tree Ship manuscript by Theodore Charrney, among many other photographs, archives, and books.